Casa Armijo was built by El Colorado Don Juan Nepomuceno Armijo in 1706. It was later sold to Ambrosio Armijo. One of the first homes in Old Town, the large adobe hacienda sits in the plaza in Old Town Albuquerque.

Throughout its years, the home has been used for a variety of purposes. During the earliest parts of the settlement of the area, it was used as a fort. Over the years, the location was under different flags: Spanish, Mexican, Confederate, Union and, finally, the United States.

Later, the family turned it into a trading post. In 1931, the location was turned into La Placita Dining Rooms, a restaurant with a tree growing in its dining room. The building was recently sold and turned into Old Town Cafe. The current owner, Michelle La Meres, is a descendant of the Armijo family.

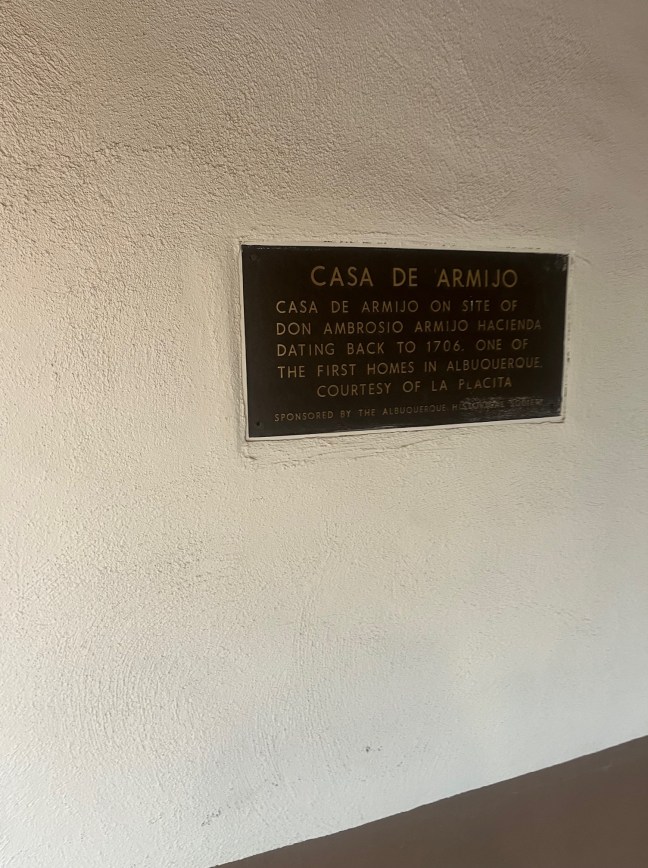

Historical Marker Inscription

(Located on front of the building)

Old Town Cafe

Casa de Armijo

Built in 1706 and occupied for many generations by the Armijo family who were prominent in local history. This hacienda was gay with social life.

During the turmoil of the early settlement the Mexican, Spanish and American Civil War occupation it was used as a fort and a refuge.

Later, still occupied by the Armijo family, portions were used as an early trading post.

In 1930 it was restored from a ruin to its present condition and remodeled in conformity with its old character.

(Located on side of the building)

Casa de Armijo on site of Don Ambrosio Armijo hacienda dating back to 1706. One of the first homes in Albuquerque.

Casa de Armijo on site of Don Ambrosio Armijo hacienda dating back to 1706. One of the first homes in Albuquerque.

Courtesy of La Placita

Sponsored by The Albuquerque Historical Society.

Location

35° 5’ 44.920” N, 106° 40’ 9.822” W

204 San Felipe St NW, Albuquerque, NM 87104, United States